When we left off, our hero (me obviously, not Ben) was in a van headed to a Mumbai hotel. The moment I arrived, two bellhops whisked my heavy bags from my hands and I knew my night was finally taking a turn for the better. Within ten minutes, I was relaxing in my beautiful, air-conditioned room on the 15th floor of the JW Marriott. It’d normally be called the 6th floor, as the hotel skipped floor numbers 2 through 10, but I agree with the hotel designer that the 15th floor definitely sounds swankier.

And then there was the free food. My sister pointed out that a large buffet was not exactly good COVID-19 infection control, but by then I’d already enjoyed it twice. And to be honest, a slight risk of death wasn’t going to keep me from three free hotel buffets a day anyway. My sister had also suggested I leave my prized collection of electronics cords behind to make room in my suitcase for a pair of sneakers, but now I was completely vindicated. By daisy-chaining cords around the room I was able to splice my Chromecast and Google Home into the hotel’s TV and internet and create a quality entertainment system.

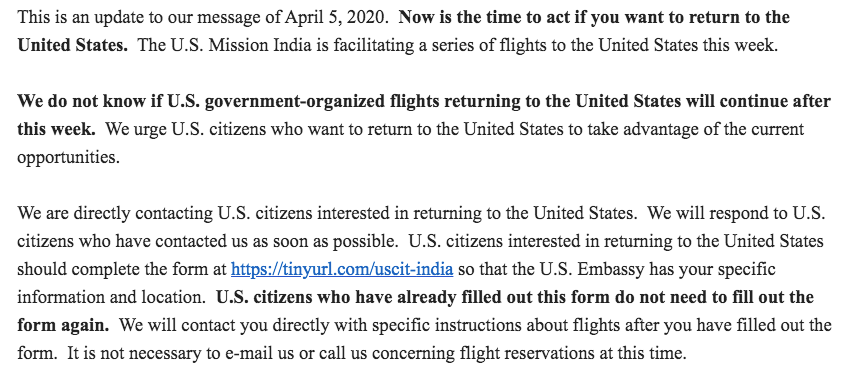

After three days of mostly relaxing (plus a little blogging– you’re welcome), we repeated the arduous trek through the Mumbai airport. This time, however, we successfully boarded the plane. Most of “the 37” had been upgraded to higher seating classes, but I chose not to be bitter and appreciate that at least I was going home and on an aisle for the nearly 17-hour flight.

Even before takeoff, I felt closer to home, as the flight attendant in my section definitely had a little attitude, rather than the typical Indian service industry deference. She was wearing a comfortable-looking Delta t-shirt instead of her dress uniform and shouted at a guy coughing in the aisle to put his mask on and sit down. She confided in the couple sitting across from me that she had sworn off doing these repatriation flights after the last one because they were such a nightmare. I’m thankful she changed her mind, because I turns out we weren’t out of the woods yet. The coughing guy wasn’t the only one still standing, and if we didn’t take off in the next few minutes, the pilots were going to hit their work-hour limit before we could get to Atlanta. To avoid this, the flight attendant heatedly told one woman she could sit in her assigned seat or stay in Mumbai, then another that it was one baby per lap and her husband was going to have to hold a child (thank god I wasn’t in that row). With 11 minutes to spare, the doors closed and we were, at last, headed home. Woohoo!

The flight was mostly uneventful. There was a line of elderly Indian gentleman waiting in line for the rest room through the entirety of the 17-hour flight, which made me glad they weren’t serving booze. And pro tip: Don’t watch “The Hate You Give” in a place where you can’t touch your face and don’t want everybody to know you’re crying.

Arriving in Atlanta was the easiest cruise through customs I ever experienced. While I had my temperature taken six times to leave India, I didn’t even fill out a customs form to enter the U.S. Unfortunately, this meant I now had about six hours to kill before my Southwest flight to Philly, two of them outside security, and apparently someone at the Atlanta airport had decided that chairs outside of security were a COVID-19 risk factor and removed them all. So I spent the next two hours savoring a Crossain’wich and coffee while sitting on a sculpture/tree planter. Aside from the prophylactic chair removal, it was pretty shocking how much more casually the US appeared to be taking the pandemic than India. Lots of employees at the airport and even the flight attendants on my flight to Philly weren’t wearing masks.

Nearly 33 hours after leaving the hotel in Mumbai (and almost five days after departing Hyderabad), my sister pulled up to the curb at the eerily empty Philly airport to greet me. She graciously agreed to host me despite my buffet-related risk taking. And I thought I could pay her back with use of my cords and electronics, but had forgotten that’s what I’ve given her for every occasion for years (I’m currently 2 1/2 months late on her 2020 birthday gift, so feel free to send suggestions that involve neither cords nor buffets).

Here at home, it is a relief to finally feel cool again (temperature-wise, that is, since I was definitely cooler in India). Am also extremely glad to be able to buy beer again, though I’m a little sad to be missing out on my Indian friends’ attempts to make their own alcohol. Also, while it’s great to have my editor on site to bounce blog ideas back and forth, I definitely don’t recommend being present to see the frowny face she makes when confronting a particularly awkward sentence. But fear not, loyal readers, despite my being back in the boring old USA, I have a huge backlog of India stories and plenty of time to blog them, so Baumerisms will continue blathering on.